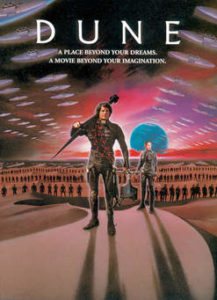

1984 saw the release of the first feature film adaptation, produced by Dino De Lauentiis, and written and directed by David Lynch the film was a commercial failure but survived to become a cult favorite.  Sixteen years later the SF channel aired a televised multipart adaptation and since then there has been talk and speculation about another feature film go at the property until recently when Dennis Villeneuve, following the success of his SF film Arrivalstarted work on a new production slated for a late 2020 release.

Sixteen years later the SF channel aired a televised multipart adaptation and since then there has been talk and speculation about another feature film go at the property until recently when Dennis Villeneuve, following the success of his SF film Arrivalstarted work on a new production slated for a late 2020 release.

So the adaptation trail has been winding and strange producing one feature film and that one considered a failure, as far as making money was concerned, however a lot of people think of Lynch’s Duneas visual masterpiece, and it is hard to argue them on the visuals, but something that occurred to me is how unlike Lynch’s other work that film turned out to be.

I am not referring to movie having a standard action plot, though it was Lynch’s first foray in the SF action, The Elephant Manis a more general public film than Lynch’s other work, I am referring to the nature of the narrative and it’s relationship with exposition.

Lynch is famous for refusing to explain his movies. In interviews he’s stated the opinion that after the film is made the scripts should be burned, as they only existed to help guide the film and their existence is no longer required after its completion. He will not explain such strange, dreamlike, and nightmarish experiences such as Mulholland Drive, Eraserhead, orTwin Peaks: The Return. Lynch devoutly holds to the idea that as an audience member your interpretation is critical to the artistic merits of a film and explanation destroys that process.

And yet throughout his version od Dunethings are not only explained, that are explained repeatedly. Plots and plans are spelling out in detail and with repetition, voice over narration, present in the original script and not a studio imposed dictate as with Blade Runner, are used the explain characters motivation and inner thoughts, a technique wholly at odds with the rest of Lynch’s catalog. Unlike the puzzle boxes of his other movies, Dune has it’s interior dissected and examined for the audience. More than anything else, this stand apart and makes 1984’s Dune the most unLynchian David Lynch film.